Mechanical loading and Genetic susceptibility to Osteoarthritis

Our research into osteoarthritis pursues the core hypothesis that all forms of osteoarthritis are caused by interplay between mechanics and inheritance. Indeed, this makes long-term joint deterioration and osteoarthritis almost inevitable in response to some kinds of mechanical event. Other forms of osteoarthritis rely mostly on inherited traits that might only accelerate deterioration. Using mouse models in which these distinct types of osteoarthritis develop, our research has continued to explore: just how susceptible joints can be to specific mechanical events, how much genetics alone contributes to speedy joint devastation and the extent that these events inter-relate.

Our research has now pinpointed specific components of joint use that produce trauma to initiate osteoarthritis. We have found in osteoarthritis-prone mice that mechanical stressors accumulation close to the articular surface in response to physiological patterns of joint loading, which are instead transferred to more distant joint sites in joints that age healthily. Our work has also made significant advances in identifying the specific gene polymorphisms that may underpin the extent to which genetically-prone mice develop osteoarthritis due to speedy deterioration. This research has been conducted to provide a clearer idea of how the development of osteoarthritis might therefore be limited, benefiting human and veterinary patients by identifying the activities that should be avoided to restrict osteoarthritis onset.

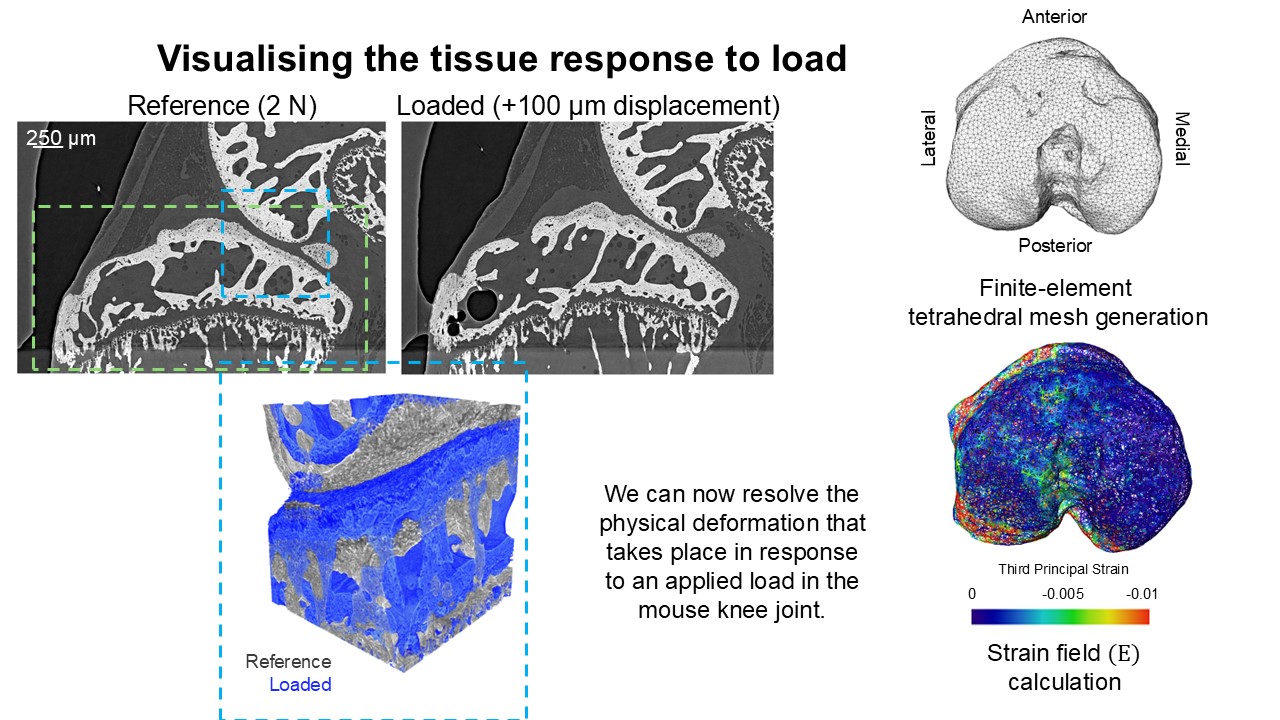

Our work has provided new approaches to control and monitor osteoarthritis. This has created a framework in which future studies might become more refined and also sophisticated enough to allow us to address how genetics and joint use/overuse interact to produce osteoarthritis – a major question in our field. We have achieved these advances in part by using high resolution imaging techniques to visualise very small mouse joints and so size is no longer a limitation (see Figure 1). This advance has meant that new questions with greater relevance to osteoarthritis in human and veterinary patients can be addressed, that couldn’t possibly have been addressed before.

Our multi-disciplinary research combined cutting-edge imaging using electron ‘beam’, creation of ‘virtual’ computer models of tiny joints, classic bioengineering to measure stresses/strains at opposed joint surfaces, and also a new mouse knee mechanical loading model. It has also made use of a mouse with an inherited predisposition to spontaneous osteoarthritis; this has already been used to test new ideas about the mechanistic origins of articular cartilage deterioration. These exciting studies show that we can slow of osteoarthritis development with a systemically administered compound which both ‘homes’ to the joint and is only ‘liberated’ in osteoarthritic environments to exert its osteoarthritis-sparing effects.

We remain hopeful that these novel approaches will identify better ways to avoid the detrimental effects of mechanical joint function and that they will provide insights into the types of stimuli that are beneficial in human and animal joint health.

Other work has identified a novel protein which plays a role in cartilage development and osteoarthritis. This new drug target was identified using a screening method utilising cartilage-like cells in 3D to mimic osteoarthritic processes in the lab, which is in line with the 3Rs principles of replacing animals in research with validated in vitro cell models. Administration of specific inhibitors of this protein stimulates cartilage cells to acquire protein networks that resemble a healthy, non-diseased cell even in conditions that simulate an osteoarthritic environment. Moreover, treatment of mice with a genetic predisposition to osteoarthritis with an inhibitor of this protein evokes similar cartilage cell responses and mouse movement is additionally improved. Positive effects are also observed in cartilage cells from dogs and horses, suggesting that inhibiting this protein could be beneficial for veterinary osteoarthritis. Together these results indicate that targeting this protein could provide an exciting novel “one-health” therapeutic for osteoarthritis.

Our work exploring interplay of mechanics with inheritance in the development of all forms of osteoarthritis has yielded major advances in our appreciation of mechanical joint function in health and disease and has pinpointed two opportunities for pharmaceutical therapeutic intervention to slow, or to potentially halt the joint deterioration that occurs in osteoarthritis.